This article was part of my submission to the Inclusivity category as part of Product Hunt’s Makers Festival. Thank you to everyone who supported, as FeMake won its category!

This project touches close to home as it represents my personal experience as a maker and as a woman in tech. More importantly, it draws focus toward gender inclusivity that I believe can only gain significance as we design the upcoming digital age.

The Why Behind FeMake

As a relatively new addition to the maker community (my first product was launched <2 months ago), I wanted to know how many people there were like me. More specifically, I wanted to know how present women were in this community.

Having worked in tech for a few years now and as an executive at a tech company for most of this year, I’ve personally experienced my fair share of bias, ranging from subtle to shocking. Since my recent entry into the maker community however, things felt different. Although not perfect, I felt supported by my male counterparts and was introduced almost immediately to Women Make, one of the most supportive communities I’ve been lucky enough to be a part of.

With all that said, the gender ratio seemed unsurprisingly familiar to my day job, and I wanted to know — where did the maker community really stand in terms of inclusion, and more importantly, why might that be?

I started by tweeting this out, inspired by a recent read of Brotopia and the news that ProductHunt had never analyzed this data themselves:

Starting a new pet project this week pulling data on female makers. I'm calling it FeMake. Things I want to know:

— Steph Smith (@stephsmithio) November 7, 2018

1) % of makers on @ProductHunt

2) % of #1 products

3) % of hunters

Etc. etc.

What do *YOU* want to know about female makers?

cc @women_make_ @rrhoover @Abadesi

Almost immediately, it was clear that I wasn’t the only one who wanted to see this data:

Bring on the data, bring on awareness and women and I'm in! Check this out by @stephsmithio ! https://t.co/5Y6QlxM1an

— María Espí (@thisismariaespi) November 7, 2018

As a data nerd I love this - please vote in the poll @ProductHunt people! 💕 https://t.co/OUN3dxiELq

— Abadesi (@Abadesi) November 7, 2018

Looking forward to seeing the data! 👏

— Kate Kendall (@KateKendall) November 8, 2018

This is a really great initiative! I know that @Abadesi has been striving to ensure Makers Spaces include a female Lead. I would love some statistics about the % of female makers on PH, and also further insights into the success (top 5, mentions in PH Daily maybe etc).

— James ✌️ (@jamesg_oca) November 7, 2018

My why here wasn’t to “out” the maker community or isolate a single statistic as not being 50:50. I think we all knew that the results would be reflective of the gender imbalance in technology, but as an analytical person, I wanted to know the numbers.

Without data in any situation, you’re flying blind. There is nothing to tether to, nothing to question, and ultimately nothing to celebrate if you are making positive changes. Moreover, if the women paving the way for future makers aren’t recognized for their early adoption, they may never get the positive reassurance to continue.

How I Went Through 40k Names

I began by pulling all the maker and product data from ProductHunt from the beginning of time (aka 2013). This was done much more quickly due to help from Toni Codina, a fellow female maker, sending me a customizable PHP script for their API. Very quickly, I had 40 thousand unique maker names that I somehow needed to align to a gender.

Unable to manually go through all 40k, I decided to feed the names through Genderize, which indicated the likelihood that the individual was “female” or “male”. For example, the name Brenden returned {“MALE, Probability: 1, Number:46”}.

Better quality vid so you can see @genderized in action. It takes a txt file of names and cycles through them, outputting a "guessed" gender, along with the likelihood of it being correct, and the count of inputs for that particular name. Pretty neat 😍 pic.twitter.com/ecr0EufolH

— Steph Smith (@stephsmithio) November 11, 2018

I knew that if I was going to report on this data, I wanted it to be as accurate as possible. So, I utilized a formula to identify certain names as most likely correct, by the following logic: if the Genderize probability was >95% and N>3, I trusted the output. Similarly, if the probability was >80% and N>10, I mostly trusted the data.

I say mostly because I still ended up manually checking 8000+ names that didn’t parse in Genderize, names that seemed to need an extra eye, or hundreds of gender agnostic names like Eli, Jordan, Pat, Sam, Charlie, Jamie, Morgan, Taylor, etc…

Naturally, there were a few cases where even when I checked the maker manually, I wasn’t able to determine the gender. Those individuals have been removed from this study.

After manually checking 8k names for too many hours, I’m confident that the accuracy of this “study” is 95%+, or at least high enough that there is now a window into the presence of female makers on ProductHunt.

Who Cares?

So, let’s take a step back before analyzing the output and quickly clarify why this even matters. As we move into the next decade, the digital products that are created will have an even greater impact on society. It’s safe to say that technology will likely have the biggest impact on human prosperity, equality, and change over the next decade.

As with anything, the more that we can achieve diversity in the people creating these products, the more diversity we will see in the products and our future as a society. Some may dismiss the importance of gender, racial, and other forms of equality, but I would argue that it is essential. And unfortunately, inclusivity does not happen naturally.

Let’s Talk Data

First and foremost, if you haven’t already taken a look at the data, you can do so at FeMake.

A few clear things jumped out at me:

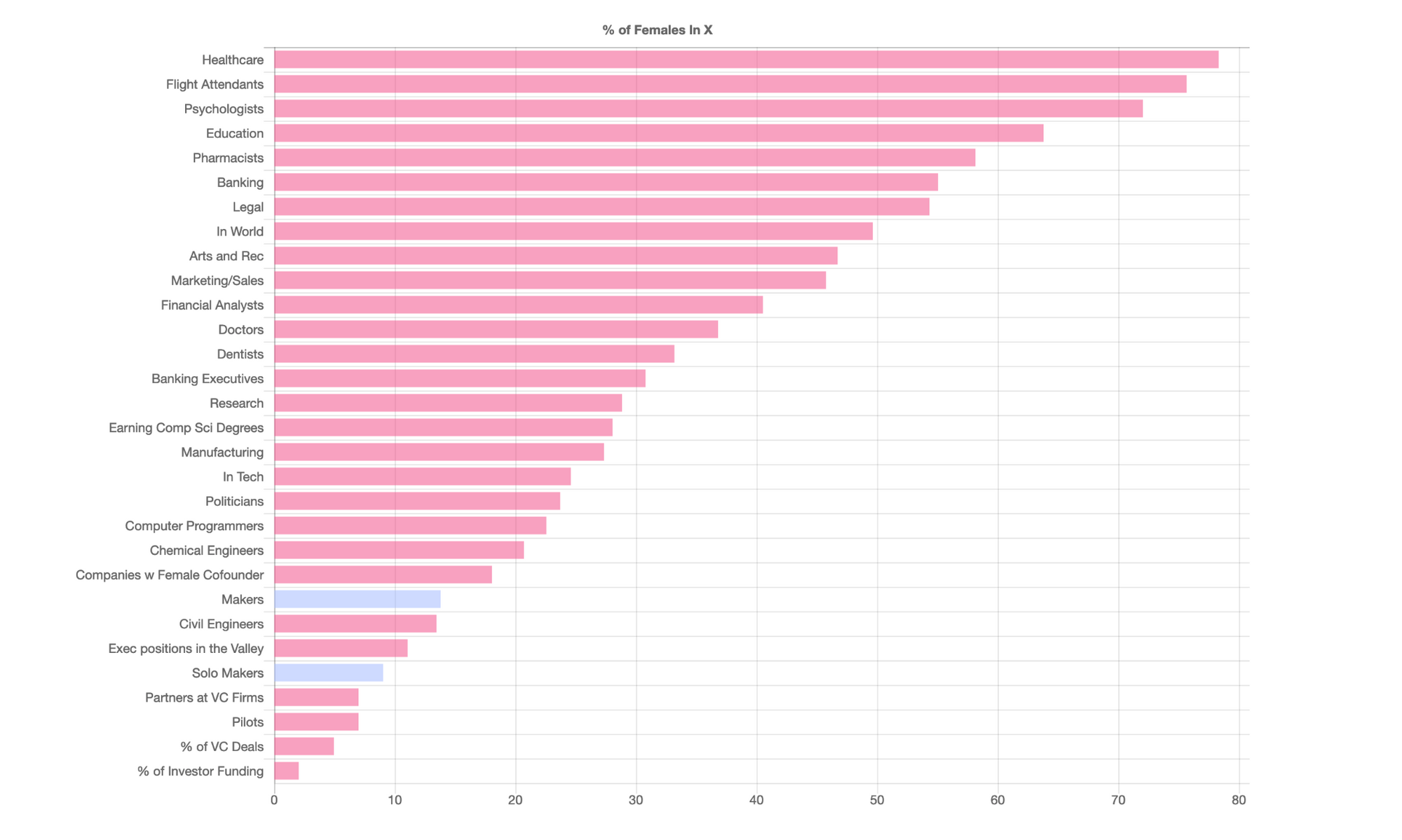

- The percentage of female makers (13.9% in 2018) was actually less than the tech industry overall. This is also improving.

- The percent of solo female makers (9.3% in 2018), ie: women submitting on their own, is even lower and not really improving.

- Average stats across upvotes, comments, products launched, and % launching multiple times are all lower than our male counterparts.

So, what does this mean? Quite honestly, I don’t have a clear answer on this. The number of women contributing is increasing, which is obviously positive and a testament to active efforts to welcome women into the community. However, the lower number of solo female makers and the lack of movement there makes me think that there is still a big psychological gap. Let me explain why.

In tech overall, there are many reasons that people often cite for the gender imbalance. (1) The pipeline, (2) psychological factors, and (3) gender bias in hiring, are three things that stick out to me and it’s unclear which of these contribute more heavily to the complex pie.

However, I hypothesize that the act of being an indie or independent maker limits the potential influence of (1) pipeline and (3) gender bias. They are certainly not removed entirely, but any person — male or female — can wake up one morning and start learning to code for $10 on Udemy or launch a no-code product. Similarly, there is no one “hiring” an indie maker or giving them VC funding; so once again, the act of being an indie maker is one that is mostly restricted by the individual itself.

The Psychology of Inclusion

Thus, although this is certainly not scientific, the findings lead me to believe that (2) Psychology is even more prominent in tech (and making) than we give credit.

I recently learned of the Cannon-Perry test that was facilitated in 1966, which forever changed the way that people stereotyped programmers (and consequently also non-programmers). In 1966, this study decided that programmers “don’t like people”, and despite this only coming from one model, it became a mechanism that self-prophesied for decades to come.

With the data pulled from FeMake and the knowledge of the skewed history of technical recruiting, we cannot stop placing importance on welcoming communities for women like Women Make and Leap, or showcasing female role models in tech. That’s one of the reasons as to why I included a resource section which you can find here.

On that note, I found it extremely inspiring to go through some of the top female contributors to ProductHunt. Not to focus on competition, but instead to center on some of the amazing products that women have brought to life, either individually or as part of a team.

Mathilde Collin, for example, is an independent female maker who has created 20 products of which most were successful, including her keystone product FrontApp. Steph Liverani was one of the co-founders of Unsplash, while Katie Zhu works on product and engineering at Medium (where you’re likely reading this).

Parting Thoughts

People will have different opinions on FeMake, but at the very least, I hope this puts a marker in the ground representing where the maker community stood in terms of inclusivity in 2018. Let’s celebrate the progress which is represented in the data, celebrate women like Mathilde, Steph, and KT, and push for more.

If you have any suggestions for data that you’d like to see on FeMake or would like to collaborate on a project that supports women in tech, please shoot me a message at [email protected]. Taking a minute to vote for it in the Inclusion category of Makers Fest will also go a long way.

Finally, if you’d like to help support women in tech financially, you can become a Patron for my work or the Women Make community.

PS: If you liked this article, you might enjoy my podcast or my latest project.

Related posts about Women in Tech: